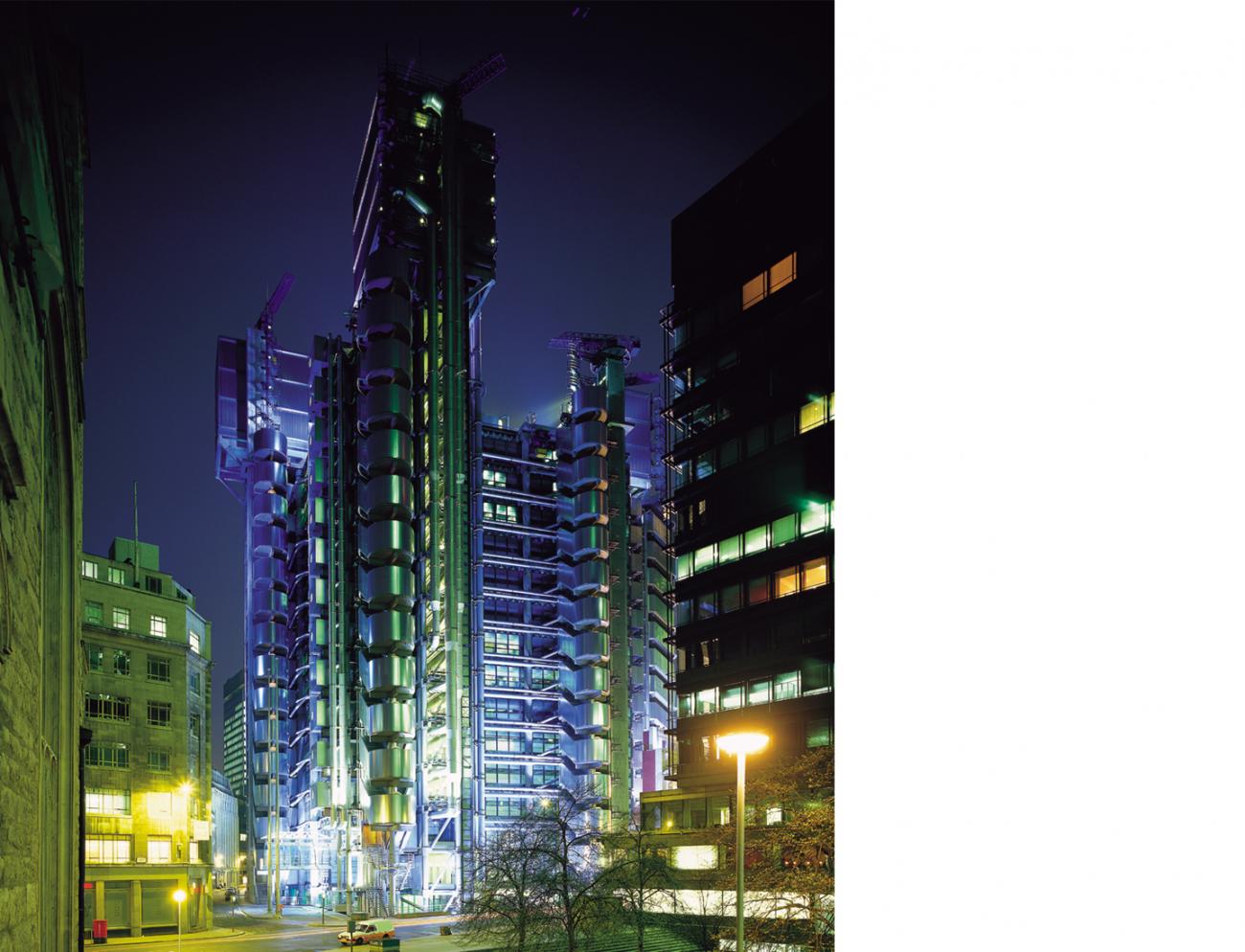

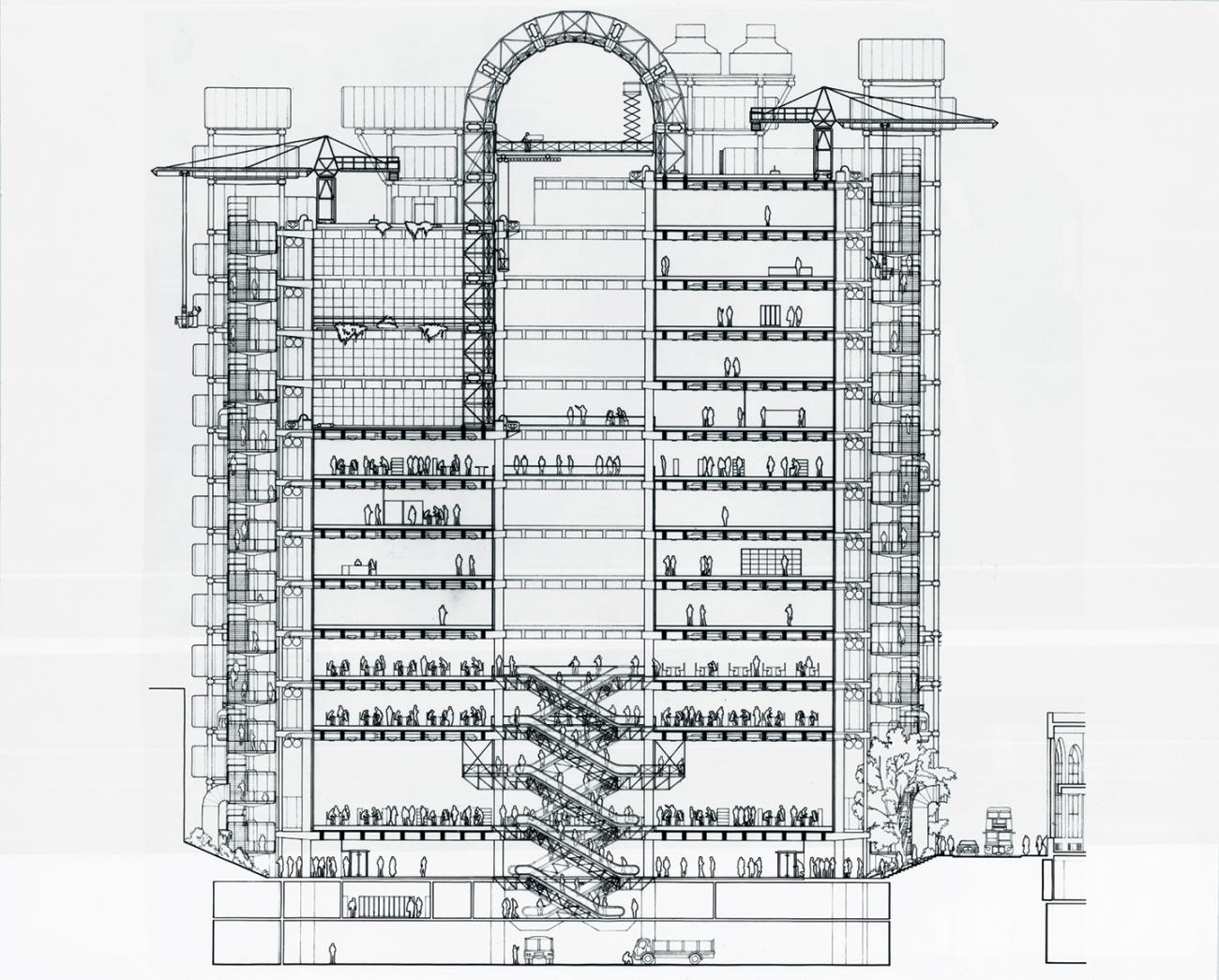

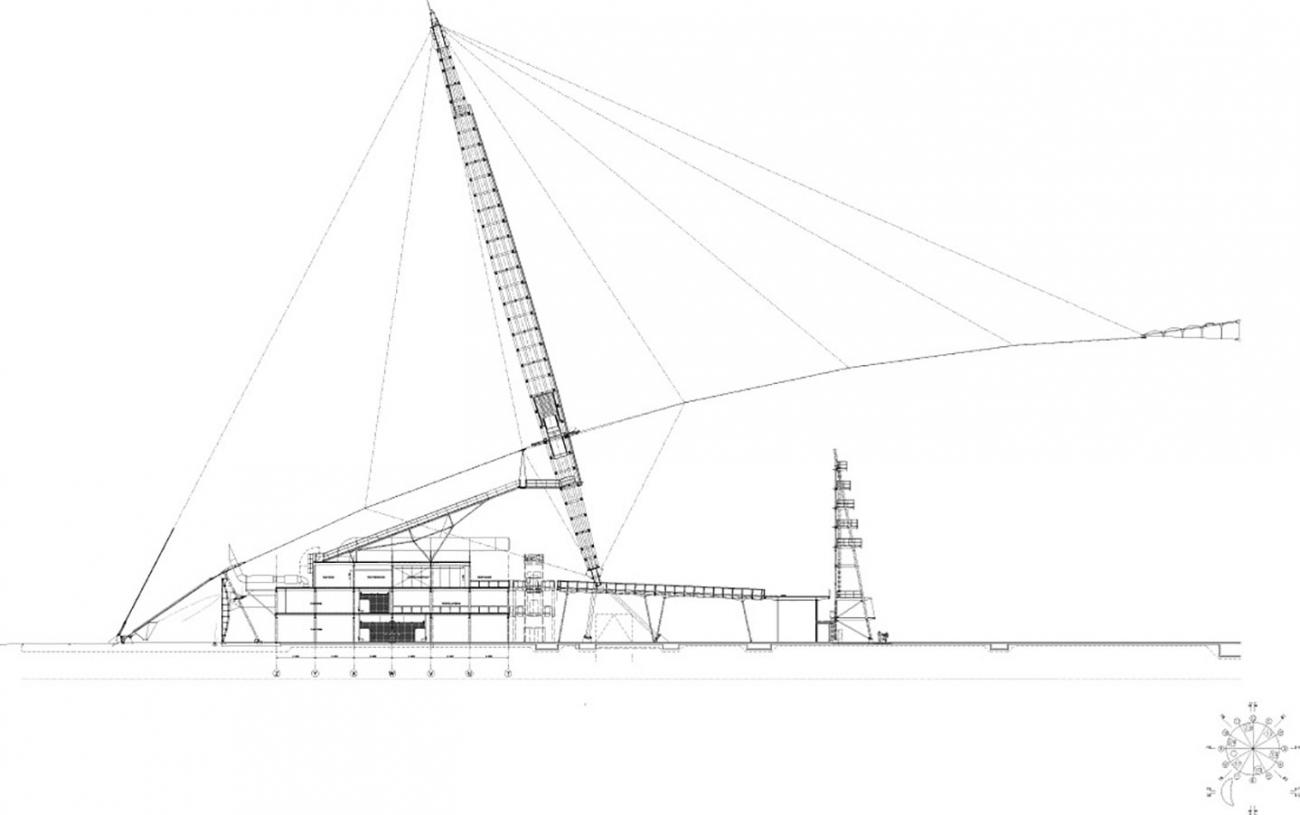

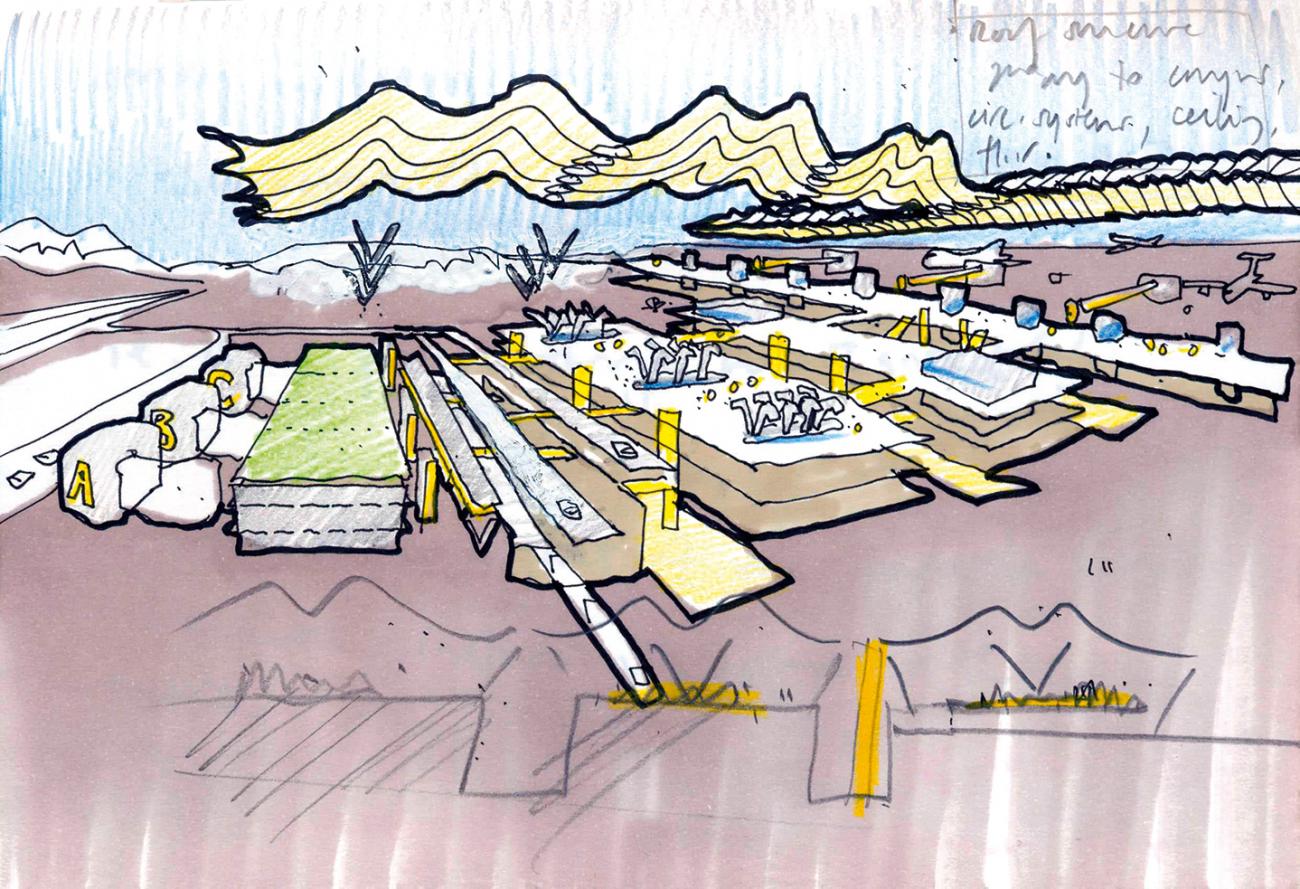

Richard Rogers (1933-2021) is best known for such pioneering buildings as the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the headquarters for Lloyd’s of London, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg and the Millennium Dome in London. His practice—Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (RSHP)—was founded in 1977, and has offices in London, Barcelona, Madrid and Tokyo. RSHP has designed two major airport projects —Terminal 5 at London’s Heathrow Airport and the New Area Terminal at Madrid Barajas Airport, as well as high-rise office projects in London, a new law court complex in Antwerp, the National Assembly for Wales in Cardiff, and a hotel and conference centre in Barcelona. The practice also has a wealth of experience in urban masterplanning with major schemes in London, Lisbon, Berlin, New York and Seoul.

Richard Rogers led an extraordinary life, from the time of his birth in Florence, Italy on July 23, 1933 to being named The Lord Rogers of Riverside in 1996, to being chosen as the 2007 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate.

At the time of Richard Rogers’ birth, his father, William Nino Rogers, was a medical student. The latter was the grandson of an English dentist who had settled in Italy. Richard’s mother was from Trieste. Her father had studied architecture and engineering, but had given up his practice in favor of an executive position with an insurance company. A cousin of Richard’s father, Ernesto Rogers, was one of Italy’s prominent architects, and a contributing editor to Domus and Casabella, that country’s leading architectural magazines. Richard’s mother had great interest in modern design and encouraged her son’s interest in the visual arts. That interest was fulfilled when Rogers served as Chairman of the Tate Gallery and as Deputy Chairman of the Arts Council of Great Britain. He is also a Trustee of the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

With war in Europe looming, in 1938, the Rogers family moved back to England where Richard soon entered the public school system, but never did very well, the reason being that he was dyslexic, not diagnosed until many years later. By the time he finished his secondary education in 1951, his family was pointing him in the direction of a possible dentistry career, but a lack of qualifications ended that possibility. In that same year, the Festival of Britain took place and brought the first officially sanctioned modern architecture to the country. Some of the fantastic temporary buildings along the South Bank sparked an interest in Richard Rogers, but National Service was the only thing in his future for the next two years. But before that, he would make a hitchhiking trip to Venice with one of his school friends. His friend precipitated a minor riot which resulted in their arrest. Fortunately, his family connections in Italy brought about release and eventually a full pardon. But that was just one of many adventures in Italy in his student days.

By the time he finished his military service, with some of that time spent in Trieste and getting to know Ernesto and his work, he had definitely decided on attending the Architectural Association, or AA as it is more popularly known. In 1959, he won the Fifth Year Prize for a school project.

In 1960, he married Susan (Su) Brumwell, daughter of Marcus and Rene Brumwell. Her father was head of the Design Research Unit (DRU), which had been formed in 1943. DRU had been a moving force in the Festival of Britain.

In 1961, the young married couple went to the United States where Richard would pursue a master’s degree in architecture at Yale on a Fulbright Scholarship, and his wife, Su, would study urban planning.

Their first home in the U.S. was with some friends of Su’s parents, sculptor Naum Gabo and his wife. The head of the Yale school of architecture was Paul Rudolph, and one of Richard’s fellow students was Norman Foster. The late James Stirling was also one of his teachers.

It was at Yale that Rogers developed an interest in the works of Frank Lloyd Wright. In fact, Rogers has said, “Wright was my first god.” While in America, Rogers, Su, Foster and another American student made a number of trips across the continent seeing as many of Wright’s buildings as possible, and a number of other works as well, including Mies van der Rohe and Louis Kahn. When they finished at Yale, a trip to California resulted in a job at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) and visits to works by Rudolph Schindler, Pierre Koenig, Craig Ellwood, Raphael Soriano and Charles and Ray Eames.